Once upon a time, there lived a few magicians who used wands made of ink, graphite or charcoal to resurrect a childhood that would otherwise be lost in time. Childhood was but a fragment of their imagination that let fairies, monsters, kings, queens and other magnificent creatures reside in the castle of their minds. The castle, often a haven away from the struggles of survival, was made of stories which felt incomplete. The magicians set out to look for parts that would make the castle whole again.

The Red Rose Girl

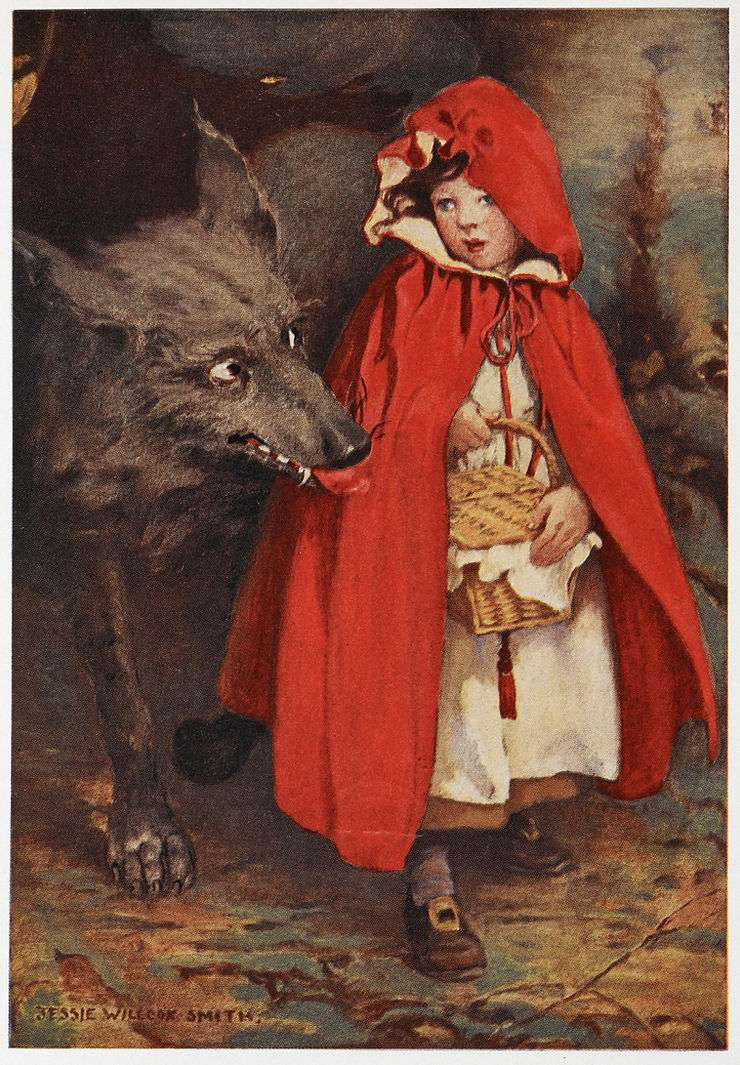

After her experience as a kindergarten teacher, Jessie Willcox Smith was certain that she was not made for childcare. While she was pursuing an education in the arts, she began to live with three other women whom she found beautiful friends in. Named after their residence, Red Rose Inn Estate in Villanova, they were called the “Red Rose Girls”, who contributed tremendously to the Golden Age of Illustration in America. It did not take her long from then to realize the magic in her, and she turned her detachment from children and teaching into pleasant depictions of childhood and motherhood. She began to see the spirit of every child in her grandniece, and put words into a spell of the eye and the heart.

One of her earliest works, A Child’s Book of Stories (1911) was a timeless spell of visuals that complemented an assortment of fables and fairy tales. Smith’s illustrations were a mirror to the children absorbing it and a portal for other creatures to engage in their childhood. The Little Mother Goose (1914) was filled with images dipped in rhymes.

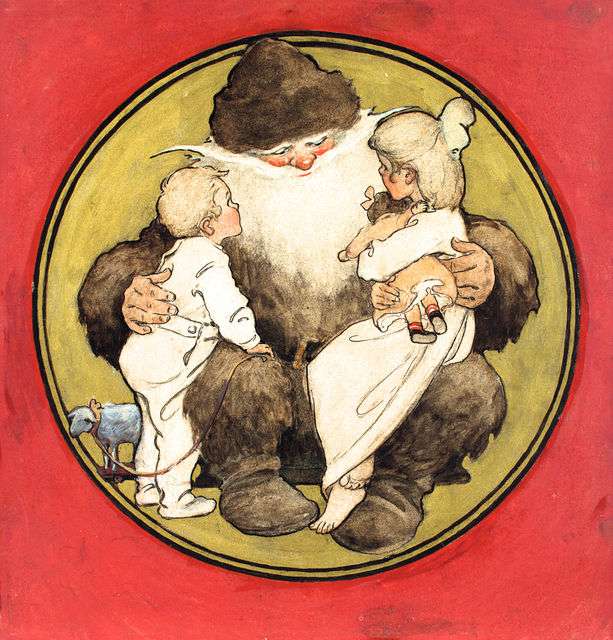

The Princess and the Goblin (1872) as well as The Night Before Christmas (1912) brought fantastical elements and figures like Santa Claus into the surface of tender minds. Stories in The Now-a-days Fairy Book (1911) and Boys and Girls of Bookland (1923) exchanged the worlds of children with elements of surprise and convincing fiction through similarities in appearance.

A Victorian Childhood

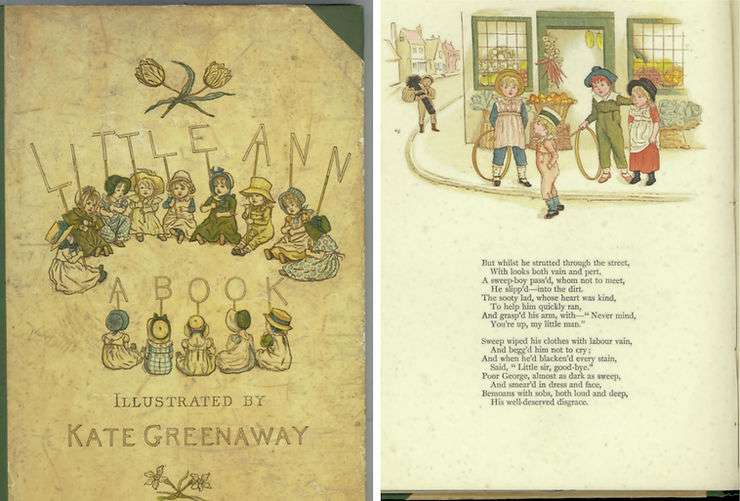

Kate Greenaway’s imagination kept her company in escaping from her erratic childhood. She found her love for drawing while struggling with an incomplete education. After receiving formal training in the arts, she began to delve into several aspects of childhood and brought back her personal experiences in a joyful, ideal tone. Her thoughts became her strength and her weakness on certain occasions. Traces from her everyday life, especially her visits to her mother’s family home in Rolleston, Nottinghamshire, and a flower garden behind the later Greenaway residence were present in her illustrations for books and nursery rhymes. Her characters included a common vision towards humans and other creatures in the Victorian era, thus shaping an accommodating bond with children.

Her first work was seen in Infant Amusements (1867), a recreation of childhood and its expectations from a child. Kate Greenaway’s Birthday Book for Children (1880) used pictorial cloth as a medium to present birthdays and seasons with amicable figures.

Although her work suffered from a disruption of style in Mother Goose (1870), it resurfaced in A Day in a Child’s Life (1881) and Little Ann and Other Poems (1883), where she focused on expectations of a perfect childhood conveyed through traditional colour vignettes and carefully crafted figures. Her last years were devoted to passing on the gift of visuals for little ones – later known as The Kate Greenaway Medal.

Colourful Chances

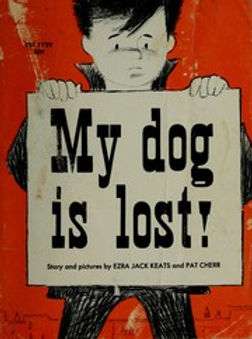

Ezra Jack Keats was recognised as a gifted child in an early age, and he realized that he was drawn to fine arts while working as a sign painter for a living. After the Great Depression, he illustrated several magazines, and eventually started engaging in children’s literature after having his work noticed by Elizabeth Riley, the then editorial director of Crowell Publishing.

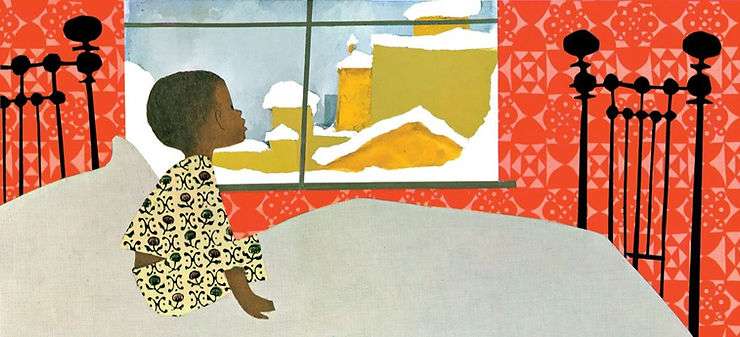

With an initial attempt at writing his own children’s book, My Dog is Lost! in 1960, Keats maintained his central characters from minority communities. His breakthrough came with the release of The Snowy Day (1962), one of his personally driven publications which reflects upon his love for experimentation. The book includes a blend of collages, cutouts of pattern paper, homemade snowflake stamps and spatterings of ink with a toothbrush. The experience made him feel “like a child playing in a world with no rules”. The central character, Peter, appeared in six more books that took the readers through his journey to adolescence. In the books that followed, he continued to engage in collages dipped in gouache, or an opaque form of watercolour mixed with gum to produce a shiny glaze. Marbled paper, acrylics and watercolour, pen and ink as well as photographs – anything at his disposal was invited to participate in the spells he cast with his work.

Here are some artists who created specimens of magic using mundane materials.

The compositions that followed with these techniques derived artistic interventions like no other. Keats never missed influences from his previous experiences as a fine artist to an illustrator for children’s books. He conjured a direct and dramatic narrative with techniques from his knowledge of the discipline. His artwork brought in a magnified range of emotions swinging from the end of soaring spirits to the dark and empty shadows of loneliness, never sustaining itself in a negotiation for long.

Where Did Alice Go?

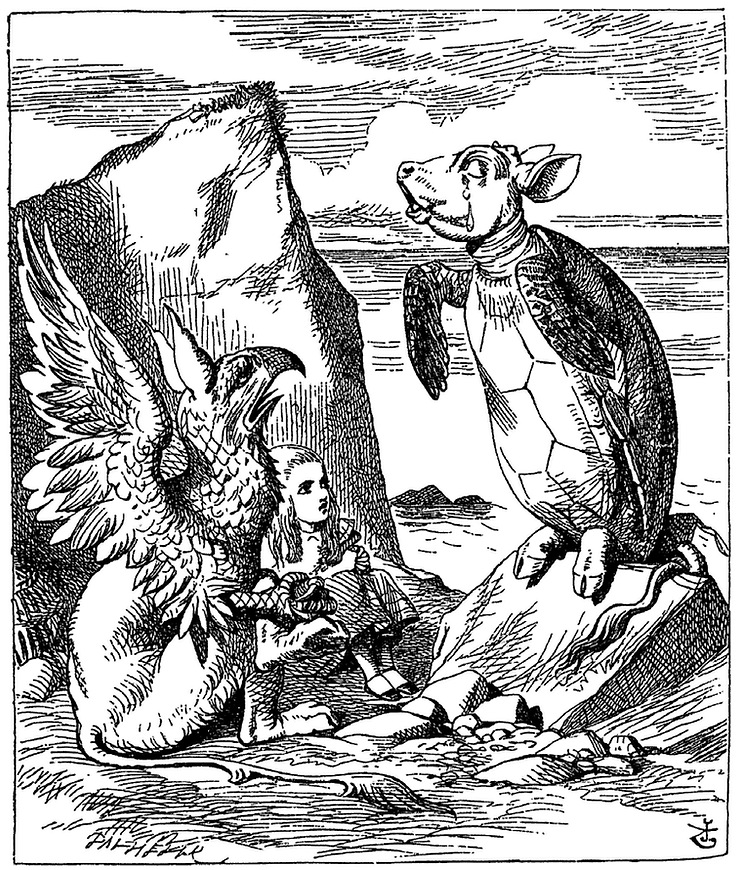

A constant feud between Sir John Tenniel and Lewis Carroll led to one of the most magnificent pieces of children’s literature. Alice in Wonderland (1865) was born not only from the penned words of Carroll, but the intricate illustrations by Tenniel.

The collaboration gave the little audience a chance to play every incident of Alice’s dream in their mind through concrete sketches while it was painted in adjectives and exclamations. Alice and the creatures in Wonderland, such as Humpty Dumpty and the White Rabbit, became part of a strict bedtime and free dreams.

While Tenniel and Carroll went on to receive acclaim in their endeavours, their conflict about artistic constraints and lack of satisfaction with the visual adaptations continued through Through The Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1871), The Nursery “Alice” (1889) and The Annonated Alice (1960). His spells held on to the spirit of childhood and the power to contain fiction against passing time.

With the knots of its imagination, art had once again untied the belief in stories. The stories found their missing pieces in the spells of the magicians, who created characters beyond words. The characters would come to life and build parts of childhood that were saved from the clutches of time. Time was defeated by artistic powers. The magicians held infant life in their wands and returned to their castle for a creative reunion. The castle was decorated with materials and memory, completed and sealed by a reward as pure as life itself. Childhood lived happily ever after.