There’s no studio door to knock on when it comes to Bhimanshu Pandel’s place and practice. The work begins in a field, beside a kiln, or mid-conversation with someone who remembers how things were done before plastic, cement and industrialisation took over.

Raised between the city and his kin village in Rajasthan, Pandel’s way of working is less about artwork output and more about listening, to landscapes, to labour, to memories and old ways of making. After studying at MSU Baroda, completing his masters at Edinburgh College of Art and then at ECAL, Lausanne, he found himself drawn back. Not to revisit the past, but to stay close enough to make sense of it. What followed were large-scale installations shaped by folk memory, oral histories, local craft, and mud, lots of it!

We sat down with Pandel to talk about sculptures that don’t stay, what it means to work without a deadline, and how trust, time, and terracotta continue to shape the way he builds.

Q1. Can you tell us about your background, your early influences, your childhood, and what first drew you towards the arts? Were there any people or experiences that shaped your way of seeing?

It all began with his grandfather and his photo-archive. “He was extensively documenting rural Rajasthan, and all his life he was a social worker working for the causes of farming communities, close to agrarian issues.”

As a child, Bhimanshu would sit through slideshows with his grandfather, absorbing images of places and practices that were already on the verge of disappearance. “At the time we were kids, so we were seeing things that were 30 years old, or on the verge of extinction; old objects and ritualistic spaces… and a lot of these things already felt lost.”

Much of his childhood was spent in the kin village. “Growing up, going to the city, that shift and change felt a bit alien, and it was something new to me.” The contrast between the two ways of living would stay with him. “Ours is an agrarian community. I recall all the important conversations among adults in the household being about agriculture and farming.” With time, that backdrop became core to his way of working. “As I grew older, it naturally became what I wanted to return to. I figured it was the only way I could understand where I come from more sensitively.”

He studied in Baroda, UK and later in Lausanne, working with materials like glass and collaborating with brands like Hennessy. “While I was working there, I realised that ideas about who I am and where I come from were so far away. I could not feel my own presence.” He found himself back home, drawn by the shifts unfolding in front of him. He started paying attention to shifts in material culture. “So much craft has been lost, potters are no longer making pots on a scale as in the past, because they’ve been replaced by modern industrial techniques.” And this awareness began to reshape his approach to practice. “The idea is not to arrive at a place, make an artwork and go back. I am interested in keeping a sense of engagement with the place alive, making something that comes from or belongs to the land and similarly becomes part of the environment.”

Q2. You’ve moved across painting, glass, drawing, sculpture, and now site-specific installations. What was your biggest learning as you shifted between mediums? Have you found something you want to stay with, or do you see that changing again?

“I have worked with a lot of materials,” Bhimanshu says, but his approach has never been about mastering one medium. “When I came back, I was working on drawings and sculptures. My process is as it develops.” What built that development early on was his effort to gather folk stories, oral narratives from the Charan, Jat, Meghwal and other communities around his village. “They represent an organic way of knowing – knowledge picked up while growing crops and farming, and isn’t taught formally.”

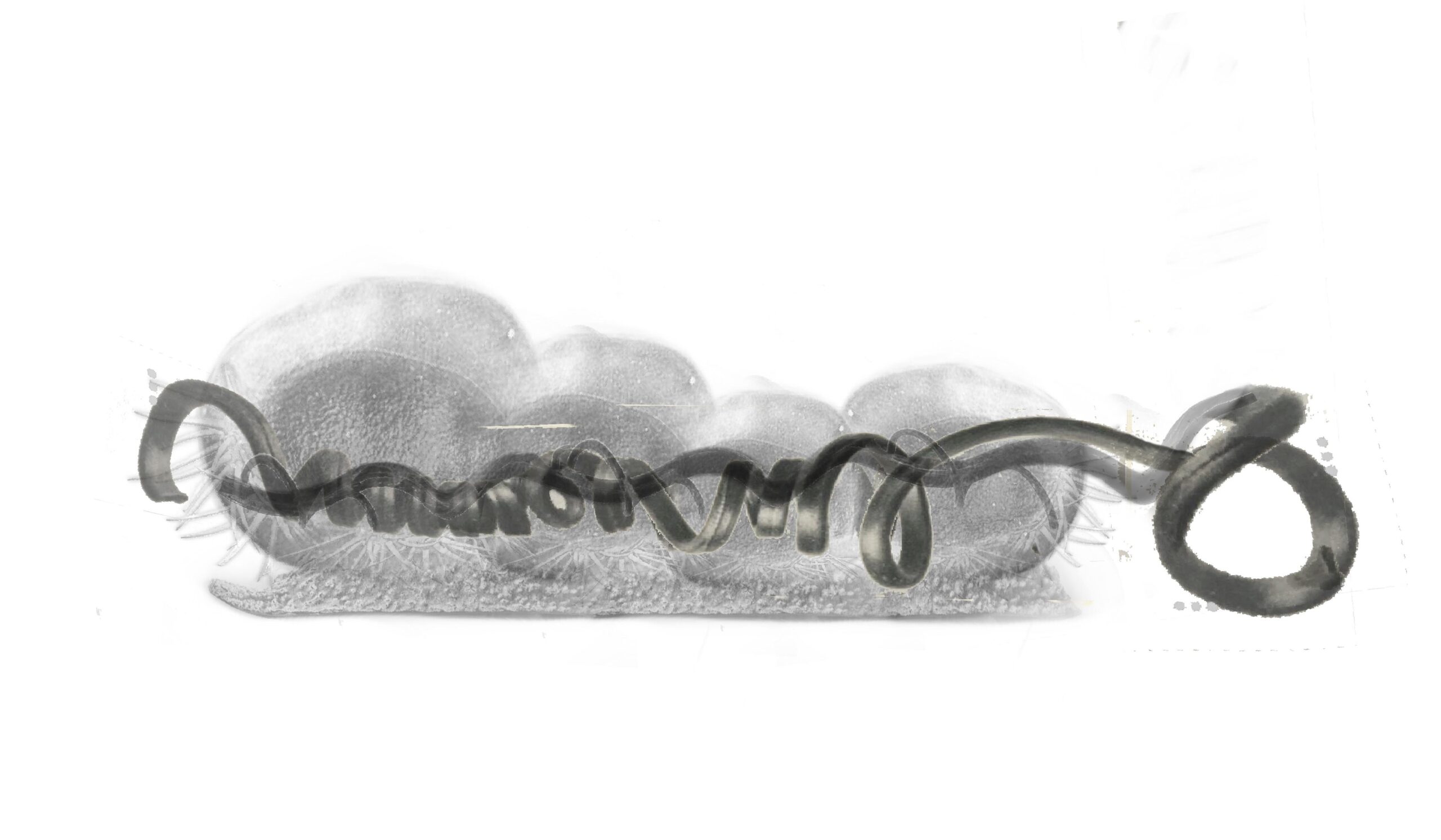

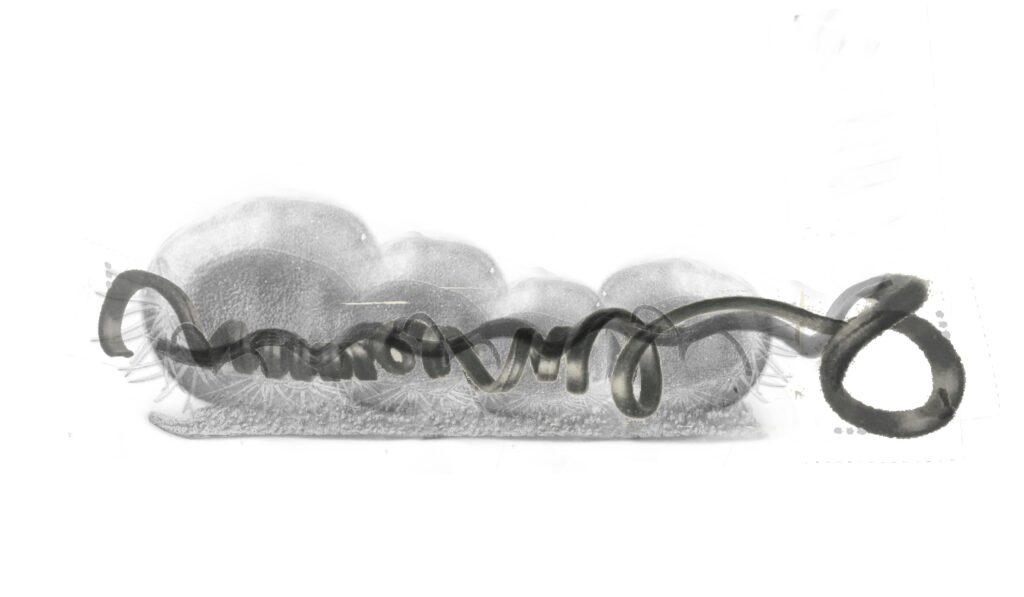

Regardless of the distance, the stories remained the same and the only thing that changed were the elements. Those stories eventually informed ‘Whispers of the Village’, his first major self funded project. “The story consists of a character named Bui, who embodies a plant, and how it is killed by an outside invader.” He began building the sculpture during COVID, with the help of school students around the area. “It emerged through spontaneous collaboration.” As the piece took shape on a water harvesting mound, it became something people recognised, responded to, and later remembered. “Eventually, there was nothing left as it eroded naturally. But people saw it and talked about it. Now it’s no longer there, and in this process, the sculpture itself came to embody a memory or a myth.”

Material, for him, is a way of listening. “The idea of a permanent, imposing artwork was not what I had in mind at the time, because materials like cement don’t carry the same folk knowledge or familiarity.” He points instead to lime and gypsum, used in older houses for their longevity and familiarity. That led him to work with lime, clay, red oxide, and hay, materials drawn from what people already knew. “I’m still experimenting, using everything, subtracting, and adding back, there’s no fixed formula.”

Q3. Your work is closely connected to your surroundings and community. But where do you see yourself in it, as an artist? Is there a personal dimension, or is it always about something larger?

Bhimanshu describes his process as embedded collaboration, one that reflects the everyday interdependence of village life. “For instance, to prepare land for farming, you need a minimum of four to five people.” This similarly translates into how he approaches his practice. Whether it’s cutting branches for basket weaving or shaping large sculptures, each step is shared.

His practice gives him a reason to work with people who hold knowledge passed down across generations. “As an artist, I am grateful for the chance to do so. The knowledge and maturity they hold, in knowing and working with local materials, is precious.”

Pandel’s collaborators aren’t his subjects or participants, they are family, neighbours, co-workers. “These materials are all sourced from the land.” Whether it’s lime from a nearby site, clay used by potters, or grass (Khempri) known for ropemaking, each element is grounded in what people already know and use.

Q4. Have there been any memorable responses from your community? Has their perspective on your work ever changed how you see it?

“That keeps changing.” Bhimanshu is clear that the people he works with don’t view what he does as ‘art’ in any formal sense.

Instead, his focus is on listening. “For me, the idea is to learn from them.”

Everyday interactions, stories, conversations, a passing comment in the fields, carry invaluable weight. “Whether it’s a story being told about a death or a birth nearby. This feeling of a close knit community informs my perspective largely”.

Q5. Your work often unfolds alongside others – artisans, neighbours, friends. How would you describe those relationships?

For Pandel, the people who work alongside him aren’t collaborators or contributors, they’re part of a much older system of trust. The bonds go far back and are generational. “The person I’m working with, I knew his grandfather, and his grandfather knew my grandfather.” Projects begin not with contracts or instructions, but with mutual familiarity. “There is an inborn trust in respect for the profession, a perspective to help which goes both ways.”

There’s no formal transaction, no hierarchy, just a rhythm of shared work. The work happens as part of the rhythm of life in the village. “We simply come together and create something.” That act of making, whether it’s building a sculpture, sourcing clay, or preparing a mound, becomes the space where observation, memory, and conversation overlap. “There are a lot of bends and breaks that come up as the labour happens, which I get to observe on a daily basis. And for now, being an observer is teaching me a lot.”

Q6. Can you talk about your recent residency in South Africa? What was that experience like, and how did it shape the way you think about landscape and process?

“We had no cell network, no Wi-Fi. We were living in tents in the middle of the desert,” Bhimanshu says. “It was located completely in the wilderness.”

Daily life was built around shared effort, cooking, cleaning, collecting materials. “There was no assigned service. Everyone just did what needed to be done to get through the day.” Even building was a collaborative task. “We used what was around: clay, hay, rocks. It couldn’t be done alone.”

The landscape felt familiar. The Mesquite tree (Vilayti Kikar or Jangli Bavalia), which grows in abundance in Rajasthan, was also found in the South African landscape. In Rajasthan, it is considered invasive, but there it holds a different cultural significance. “The food storage structures called silos in South Africa and kothis in Rajasthan, roof-making techniques etc., were very close in structure to what I’ve grown up seeing.” Materials held knowledge shaped by survival. “They used ant sand because it holds silica and can withstand weather. It wasn’t something that was taught formally, but forms of knowledge that had stayed in the community across generations.”

He began to notice how knowledge moves quietly across regions. “It’s the way myths travel. The story changes, but what is at the crux of it stays.” In Rajasthan too, he says, most of cultural folk history wasn’t written. It is passed on through stories, conversations, and memory.

To read those layers, he turns not just to people, but to books that help frame what he’s sensing. “Writers like Derrida and Levi-Strauss taught me ideas of how the past sits in the present,” he says. “And these ideas have shaped how I look at the world around me.”

Q7. You’ve worked across mediums, studied in different countries, and returned to build something rooted where you began. For younger artists watching this trajectory, what would you say to them? Is there anything you’ve learned that took you by surprise?

Bhimanshu doesn’t position himself as a guide. But when asked what he’d offer to someone hoping to follow a similar path, he returns to a line from a mentor that’s stayed with him: “There is nothing we can give or take from them, because they are in a much greater position than we are.”

It changed something in him early on. “If we could learn two more things by being genuine and honest, I think that’s all it takes,” he says. “To be true to yourself, the questions or the concerns you want to address, be honest about it. That automatically gives the work its ingenuity. I do speak from a place of relative privilege, and I try to work and move with this awareness.” The people he works with aren’t engaging in art discourse. Their concerns are direct, lived. “You have to find ways to be similarly immersed in it,” he says.

Q8. Was there a point when this way of working started to feel right to you, or was it something that revealed itself slowly?

“It was a gradual process,” Bhimanshu says. There was no single decision, no sudden clarity. “I wasn’t trying to deal with it as you would a concept.” Instead, his practice developed through repetition – trying, adjusting, starting over and over again. “You do one thing, you learn something, then you do another thing and you learn something else. Maybe you combine the two, maybe it doesn’t work, so you try to do it again a different way.”

That rhythm, slow, iterative, and unforced, has shaped his entire working process. “I’m trying to keep this approach because it keeps me grounded. I don’t like to rush.” Waiting for a big idea, he says, has never helped. “It then becomes a formal concept to me, and loses its ingenuity.”

Q9. You’ve chosen to work outside formal art centres and build something on your own terms. For artists trying to do the same, what would you say? And how do you navigate the expectations of institutions while staying rooted in your own process?

“If an artist doesn’t have the freedom to work or ideate, then what’s the point?” Bhimanshu asks, not rhetorically, but as someone who’s actively built a practice outside conventional formats. His projects often begin without fixed deadlines, and rarely with a gallery in mind.

One such project was initially meant to take two months. “But I took six months because that is what the work needed,” he says. “The institution was very accommodative about it. If done with sincerity and transparency, they do allow the artist the space needed to let a work evolve.”

Q10. What do you do when you’re stuck or unsure of where the work is heading? Is there anything outside of art that helps you navigate those moments?

There are times when the sculpture doesn’t move forward. In those moments, Pandel turns to the land, for a different kind of making. “It gives me a lot of freedom to think with renewed perspectives.”

Lately, that’s meant working on a large-scale water harvesting project. “We are digging dams in the field to contain water, so that we can farm our fields. The fields we have come from wet sand, so it can hold water without the use of polythene spreads.”

He spends his mornings and evenings walking at the site, watching how it changes. “I go and observe how the landscaping takes shape gradually.” It moves at its own pace, but always with a clear sense of place. The land keeps changing, and the work changes with it. Sometimes the drawing is slow to come, but staying with the site helps him figure it out.

Q11. Is there anything you’ve been reading, watching, or listening to, especially from your local community, that’s shaped how you think about your work or added new layers to it?

Over the years, there have been many inspirations, but he doesn’t move fast through the media. A few films, a few books, and revisit them again and again. “Even if you spent your whole life consuming it, it wouldn’t end. So I try to stay with a few, and relive them.”

Abbas Kiarostami’s films are one of those constants. The way Iranian new wave cinema unfolded, political shifts, village life, folk concerns, offered something he could recognise. “They were showing what life really looked like, and that visual language stuck with me.” He also mentions Arabian Nights by Pasolini, a film he returns to often. “It’s built from folk stories, mythical stories, but done with rawness. There’s no need to polish or decorate it. The simplicity is what makes it work.”

Lately, he’s been reading ‘The Blind Owl’ by Sadegh Hedayat and the writings of Juan Rulfo, whose texts he connects to the visual tone of magical realism. You won’t always find them on the surface, but they hold steady in the way he approaches form, rhythm, and place in his works.

Q12. What’s been on your mind lately, are there any thoughts, concerns, or questions that are guiding where your work might be headed next?

There’s no show being planned at the moment. Bhimanshu isn’t in a rush to exhibit. “The practice is still developing. I want to give it time.” He’s preparing to travel, first to Austria, where he’s been invited for a residency in Salzburg that focuses on cultural studies. Then to Argentina. Both, he says, are opportunities to stay in a space, observe, and gather experiences without thinking too far ahead. “I’m really looking forward to it. But I’m not going there to build a show. It’s about understanding more, developing the work slowly.”

Back home, he’s also been setting up a clay studio, where he’ll be working on terracotta firings on a large scale. He’s learning traditional roof-making techniques and trying to work with local methods. Drawing continues alongside, but nothing feels urgent. “There are a lot of experiments I’ve been thinking about. Some are still in process.”

Exhibiting will happen eventually. But he doesn’t want to make work with that outcome in mind. “A show isn’t something I need to prepare for separately. The work I’m engaged in, whenever it’s ready, that’s what will make the show.”